Infrastructure: Transportation projects moving along

By SAUL CHERNOS

Asphalt Bridges Construction Infrastructure RoadsDespite economic, supply chain and labour challenges, road and rapid transit projects continue to take steps forward.

Supply chains continue to be stressed, labour shortages remain chronic, and the economy is delivering inflation and recession. Yet road and rapid transit projects enjoy considerable momentum across Canada even as the various players manoeuvre, with varying degrees of success, to obtain approvals and keep financing and timelines in order.

BILLIONS IN ONTARIO PLANS

Ontario offers a classic illustration of the drive to expand transportation capacity. The Toronto area is growing rapidly and the current provincial government has been jockeying to expand the network of roads and bridges to alleviate congestion.

“We have $785 million worth of goods per day traveling on our highways, and we know that the population of the Greater Golden Horseshoe, alone, is expected to grow to almost 15 million people by 2051,” says Andrew Hurd, director of policy and stakeholder relations with the Ontario Road Builders’ Association.

The Bradford Bypass, a high-profile $800 million project that stands to connect Highways 400 and 404 north of Toronto, was taken off the table by an earlier provincial government but was subsequently revived, and its future looks promising. Early work began last fall on a bridge crossing the bypass near Yonge Street, and environmental assessment work could be completed by year’s end. A second major project northwest of Toronto, Highway 413 appears to also be moving forward as well, although it continues to face a possible federal environmental assessment even as it undergoes preliminary design.

Hurd is optimistic that both projects will succeed and says, despite inflation, supply chain pressures and a tight labour market, the roadbuilding segment remains strong across the province.

“We’re looking at approximately $87 billion over the next 10 years,” Hurd says, drawing on government budget numbers to peg highway and bridge construction in Ontario at $3 billion and public transit at more than $8 billion over each of the next three years.

“It’s a strong outlook,” Hurd says, contextualizing transportation as the backbone of the province’s domestic and export-driven economy. “With immigration increasing, with more people coming to Ontario, we think it’s essential that infrastructure projects such as Highway 413 and the Bradford Bypass are built as part of a multimodal strategy to keep Ontario moving.”

The $3 billion annual figure for Ontario’s roads and bridges includes roughly $2.3 billion worth of rehabilitation and expansion work. Crews are currently widening Highway 401 in Mississauga and Milton, improving Highway 7 between Kitchener and Guelph, and rehabilitating the QEW Garden City Skyway, which includes a new twin bridge over the Welland Canal to connect St. Catharines and Niagara-on-the-Lake.

Design work is also underway on a replacement of the aging Frederick Street Bridge in Kitchener, and EA and engineering is slated for later this year for a dedicated passing lane on Highway 11 north of North Bay. In the northwest, the province is looking to widen Highway 17 from Kenora to the Manitoba border.

Rapid transit projects have also been active. Despite delays and rising costs on light-rail lines in Ottawa and Toronto, new routes such as downtown Toronto’s Ontario Line are breaking ground.

RAILS AND ROADS TO THE WEST

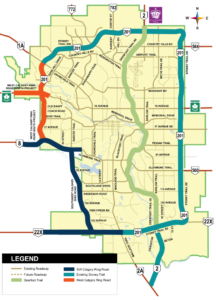

Activity is also strong out west. Alberta Roadbuilders and Heavy Construction Association CEO Ron Glen says Calgary West, the final segment of a substantial Ring Road undertaking, should be completed in about a year, and crews are working on Edmonton’s Yellowhead Trail Freeway conversion, assorted bridges, underpasses and rehabilitation projects, and an overpass on Highway 1A near Cochrane.

Future plans include twinning Highway 3, the southernmost east-west connection between Saskatchewan and British Columbia.

Public transit projects, meanwhile, include extending the Edmonton Valley Line West and Valley Line East LRTs, though the latter, like light-rail lines in Ottawa and Toronto, is behind schedule. Calgary, meanwhile, is planning its new Green Line LRT as a P3.

For all the activity, however, Glen says municipalities anticipate reduced provincial funding over the next few years, which could impact transportation capital programs. One provincial project has faced a significant struggle: The province halted plans last year to employ a P3 to upgrade Deerfoot Trail, a major north-south freeway in Calgary, opting instead to procure the bulk of the plans in smaller, more manageable sections. At the time, transportation minister Prasad Panda said pricing volatility and historically high inflation in the construction sector meant a P3 approach was no longer economically viable.

“We will focus on improving the most congested areas on the highway first to improve traffic flow and reduce travel times for commuters in the Calgary region,” Panda said in announcing the change.

Work is underway to identify the most critical areas for improvement that can be tendered and completed as quickly as possible, and the province has pledged $210 million towards sections deemed highest priority.

Of course, when the province finally changed course from the P3 plan, $15 million worth of design work already completed by the three consortiums vying for the contract “was just shot out the window,” Glen says. The ARHCA is pressing the province to establish a new highway trust company to manage projects and make the process more predictable and stable.

“As soon as you start getting really complex you increase the risk,” Glen says. “Fluctuating interest rates makes it very risky to do these risk transfer projects.” Uncertainty and risk aren’t always dampers for transportation projects, however. In British Columbia, chaotic weather is actually driving construction. Kelly Scott, president of the B.C. Road Builders and Heavy Construction Association, says rehabilitation and flood-proofing continues along sections of the Coquihalla Highway where intense atmospheric river rainfalls damaged roads and bridges in late 2021.

“They’re engineering it so it can withstand 1,000-year floods like the one we had,” Scott says, describing work improving dike systems along the Lower Mainland and enhancing bridge abutments to strengthen vulnerable pinch-points. Crews are also adding layers of rip-rap and other armour rock along riverbanks where the worst flooding occurred to prevent erosion and keep the river in the riverbed.

“Emergency repairs have been completed and we’re now improving the pinch-points to make them more climate resilient,” Scott says, noting significant upgrades to three bridges.

As with the other provinces, additional routine activity is ongoing. Projects range from the Pattullo Bridge replacement in the Lower Mainland, to ongoing widening along Highway 1 from Kamloops to Golden, and an expected announcement about widening towards Chilliwack.

“It’s recognition that the Port of Vancouver needs to have a dependable infrastructure system to ship goods across the world,” Scott says, forecasting three to four years of work.

“I think you’re going to hear more about investments in a national infrastructure corridor through the ports of Vancouver and Prince Rupert,” he says, noting that climate change impacts on infrastructure and the economy have stakeholders investing to build back better.

THE NEED FOR A NATIONAL APPROACH

While transportation projects are strong in Ontario and Canada’s two westernmost provinces, crews are busy from coast to coast to coast. From Highway 104 improvements in Nova Scotia, to tunnel and bridge work in Quebec, to new all-season roads in the far north, each region has its own narrative, but Canadian Construction Association president Mary Van Buren describes transportation infrastructure as a national imperative requiring ongoing attention.

The CCA’s most recent infrastructure report card, released in 2019 before Covid throttled the global economy, noted 40 per cent of roads and bridges in fair, poor or very poor condition.

“It showed there’s a need to fix what we have,” says Van Buren. “As a nation we need to invest in order to enable our economy.”

With the Investing in Canada Plan allocating $180 billion over 10 years for everything from public transit to climate change impact mitigation, to enabling rural and northern communities, she acknowledges the federal government is paying attention. Still, 65 per cent of Canada’s GDP comes from trade-enabling infrastructure, and she says the country is under-investing relative to other strong exporters such as Australia and the United States.

“One of the challenges is that, as a nation, we don’t have a long-term infrastructure plan. Everything tends to be done on political cycles.”

Van Buren is calling for a 25-year plan prioritizing infrastructure spending. “That would allow us to line up the labour force we need and would give confidence to businesses and industry to invest in technology, to invest in greening — all those things,” she says. “Otherwise, we can fall into boom-and-bust, which isn’t effective or productive.”

LIMITED BY LABOUR?

While long-term planning could address the shortage of skilled workers, unemployment in construction remains chronically below historical levels.

“The availability of labour will continue to have an impact on project schedules, particularly in regions where labour market tightness is particularly acute,” says Bill Ferreira, executive director of BuildForce Canada, which specializes in labour market analysis.

Still, he points out the shortage isn’t unique to construction. It reflects a broader demographic reality, with 20 per cent of Canada’s population between the ages of 50 and 64, and only about 16 per cent of the country’s population under the age of 15.

“More people will be entering into retirement than will be available to backfill for those individuals,” he says. “The scarcity of young people means competition for young talent is going to be incredibly intense.”

Ferreira says immigration can help maintain a core working age cohort, as can promoting careers in the skilled trades, and the industry continues to engage people who have historically been underrepresented.

“We’re starting to see positive signs. When we look at apprenticeship registrations, particularly in the Red Seal trades, we’re starting to see the number of women registering in programs is just under six per cent now. That’s up from about three and a half percent ten years ago.”

The sector also collaborates with Indigenous communities and businesses. “It depends on the region and the size of Indigenous communities,” Ferreira says.

INFRASTRUCTURE TO SHOW RESILIENCE

Labour market and economic uncertainties notwithstanding, Pedro Antunes, chief economist with the Conference Board of Canada, says signs point to a gradual recovery and relatively strong prospects for infrastructure. Steadily increasing immigration, especially in larger urban centres, necessitates improved mobility yet also helps supply labour power to keep projects moving.

“We’re seeing a supply of workers coming in available to work and a lot of organizations picking up those workers because they’ve been having trouble meeting demand,” Antunes says.

The same duality applies to economic pressures. Inflation has sent costs soaring, yet higher price tags have enabled tax revenues, helping raise funds for infrastructure.

“Weaker economic growth this year is going to stress a lot of governments, and some of them will see weaker revenue growth,” Antunes says. “But I think the fiscal situation is better than it was looking even a year ago.”

One source of financing aimed at helping projects deemed particularly worthy but otherwise vulnerable is the Canada Infrastructure Bank. The Crown corporation currently has $3.7 billion invested in rapid transit and trade and transportation buckets, with a view to helping finance projects meeting federal imperatives such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and serving remote regions.

Two of its higher-profile projects include the rebuilding of the New Westminster Bridge, which provides rail service to the Port of Vancouver, and modernizing Tshiuetin Rail Transportation, a freight and passenger service connecting three northern Quebec First Nations.

“Our mandate is to be a force to unstick important projects that wouldn’t otherwise get done. We have the ability to be patient capital and wait until demand ramps up for repayment to start, where traditional lenders wouldn’t be able to wait,” says CIB chief investment officer John Casola.

“It doesn’t matter what your political perspective is — at the end of the day there’s very little disagreement about the fact that we need lots of important infrastructure in this country.”