Taking shape: 3D printing revolution on the horizon

By Jillian Morgan

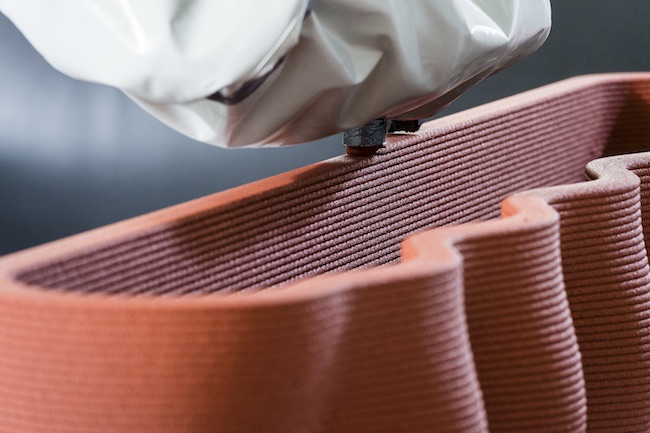

Concrete Construction MaterialsAt Sika AG’s research facility in Widen, Switzerland, the nozzle of a 3D printer pumps out billowy concrete at one metre per second. The material cures almost instantly, just in time for the machine’s printing arm to deposit the next layer. In a steady, continuous movement, it brings a distinctive structure to life.

Gearing up to release its first commercial printer at the end of the year, Sika is one of several to industrialize the process. At volumes up to four tons per hour, the printer promises to push out concrete “so rapidly, inexpensively and precisely that it can be used on construction sites,” the company announced last June.

That volume is in another league compared to the majority of 3D printers on the market, which typically peak at 100 to 200 kilograms per hour, according to Frank Hoefflin, the company’s chief technology officer.

“You can make some really nice things [with those models]. You can even build some little bridge and balconies… But they’re not really interesting for the construction industry,” he says. “For the construction industry to be [interested] we’re looking at three to four tons per hour. That’s a different ballgame.”

The concept of 3D printed structures isn’t new, though the technology has gained traction in recent years, particularly in the residential sector as a method to quickly build homes at a fraction of the cost.

“When you look at the construction industry, in general, it’s the one area that has seen the lowest productivity over the past 80 years compared to any other industry,” Hoefflin says. “Part of the reason is, of course, you have some very basic materials like concrete that really haven’t changed for many years.”

The process of mixing and pouring concrete, though fine-tuned in some respects, has largely stayed unchanged for the last 50 years, he says.

“3D printing is clearly an attempt to change this – to allow the industry to gain, on one hand, a lot more productivity, but also give it the opportunity to go to new frontiers,” Hoefflin adds.

He isn’t the only one to see the value of 3D printing in construction.

The Conference Board of Canada released a report in November 2018 analysing the potential of 3D printers to build homes in remote Northern communities, where high construction costs make it difficult to address the region’s housing shortage.

In Nunavut alone, the cost to construct a new public housing unit can cost upwards of $550,000 – three times the cost of building the same unit in Toronto – according to the not-for-profit think tank. The report estimates the cost of 3D-printed homes could be one-fifth of that number and take considerably less time, with a 400-square-foot house constructed in the span of 24 hours.

“While it’s not yet clear whether the technology can address or overcome some of the key issues that construction projects must contend with in Northern and remote environments, it’s not hard to see how 3D printing construction could potentially have a meaningful impact in Canada’s North,” Stefan Fournier, associate director of Northern and Aboriginal Policy at CBoC, said in a release.

3D printing would leverage locally available materials and reduce reliance on the shipment of construction supplies to isolated communities, CBoC says. It would also allow for design flexibility, which could aid in designing homes that “reflect local culture and values.”

For Hoefflin, that flexibility is a key advantage of 3D printing, which allows the industry to go beyond boxy structures.

“This is what the construction industry has been optimizing for the past 100 years: how to build a straight wall,” he says. “That’s why most buildings are just regular flat, straight surfaces with a 90 degree angle.”

3D printers won’t replace traditional concrete pouring, Hoefflin says, but the equipment could facilitate the construction complex building designs without the added cost.

“Eventually, this type of technology will go much further than just building parts of buildings,” he says. “I think there will be a lot of impact to the service industry. Eventually, a lot of companies will pick up equipment like this and will be able to work together with interior designers and others to really provide a very high degree of individualization to the building industry.”

This article first appeared in the April 2019 issue of On-Site. You can read through the full issue here.