Carrying on: Canadian infrastructure market shakes off COVID-19, poised to put stimulus funds to work

By David Kennedy

Infrastructure

Recent work on a Trans-Canada Highway widening project on Vancouver Island. Infrastructure work has continued across Canada despite of the pandemic. PHOTO: B.C. Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure

Between deserted highways, abandoned schools and empty rail cars, much of Canada’s infrastructure has never been as underutilized as it was in April and May. Health care facilities and telecommunications networks, on the other hand, have rarely been so strained.

Through it all, as the economy ground to a halt and questions swirled over whether Canadians would ever be coaxed back onto subways or into classrooms, construction kept inching forward on new transit projects, new schools and new public works that presumed the country would emerge from the pandemic into something resembling normal.

“Contractors found a way to keep reasonable productivities going,” says Gary Webster, the national leader of KPMG Canada’s Infrastructure team, as well as the firm’s global head of Capital Projects Leadership.

“COVID didn’t have as big an impact on the construction industry as we originally worried about,” he added. “A lot of things carried on.”

Bill Ferreira, executive director of BuildForce Canada, credits the industry’s focus on safety and its ability to adjust to new circumstances for the large number of sites able to remain active.

“I think what we’re seen over the last three months is just how well this industry can adapt in a very short time frame,” he says.

It is an attribute that is particularly important on the infrastructure side of the business.

“The reality is, [for] civil work, you have to be very adaptable,” Ferreira says. “You’re always dealing with potential delays related to weather, soil conditions. This is just one additional layer. There are added expenses obviously as related to providing PPE to workers, but by and large, social distancing is a little easier to do when you’re in an outdoor environment.”

But unlike retail and hospitality, and other industries that took hard, short-term hits from COVID-19, the pandemic’s effect on Canadian infrastructure is likely to play out over a matter of years.

Paul Gill, the National Valuations leader and a partner at accounting and consulting firm BDO Canada, expects a large amount of capital to move into infrastructure in the months ahead, but cautions that when, and if, Canada returns to the status quo will determine what areas of the sector will see the biggest benefits.

“Are there going to be changes in funding? Or going to be changes in priorities when it comes to infrastructure?” he asks, adding that for now, governments are generally continuing to push forward with plans already on the books.

“The long-term view is that things are going to get back to normal,” Gill says. “As long as that thesis still holds and the world’s not going to fall apart… by the middle of next year, things will start to really get back to normal.”

But with a highly fluid situation persisting in all industries, uncertainty remains unavoidable.

CHECKING IN ON THE IICP

Front and centre in previous years, COVID-19 has relegated the federal government’s $187.8 billion Investing in Canada Infrastructure Plan (IICP) to the back-burner in 2020. Despite being out of the limelight, spending has continued, and prior to the pandemic, Ottawa was regaining some of the ground lost to delays early in the spending plan.

In the latest PBO assessment, the federal government has picked up the pace on infrastructure spending. PHOTO: Getty Images/Ollo

The latest assessment from the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), released this June, found investments under the plan remained delayed, but the lag had lessened since its previous check. The PBO estimates a total of $51.1 billion spent on approximately 53,000 federally-backed infrastructure projects coast to coast since the start of the IICP. The figures, which factor in reporting from fiscal 2019-20, indicate the federal government is about $2 billion short of its planned investment level for the first third of the 12-year initiative.

In terms of job creation, the PBO said the infrastructure plan has generated about 91,400 full-time equivalent positions over the past four years. It added that without the delays in spending, about 4,400 more construction workers would have found a place on job sites.

It is still too early to measure the effects the pandemic may have on the tens of thousands of projects under the 12-year spending plan, but most ongoing work was deemed essential and allowed to continue through the spring shutdowns.

Though COVID has sown some doubt about certain categories of infrastructure — transit that relies on packaging as many people as possible into a rail car, for instance — for the time being, governments are expected to continue pushing ahead on their existing agendas.

“I think everyone is looking at COVID-19 as a blip,” Ferreira says. “I don’t think at this point anyway that it is going to fundamentally change design forever.”

To date, Ferreira added, there has been no indication governments across the country intend to overhaul their infrastructure priorities as a result of the pandemic. In fact, after a brief pause in new funding announcements in April and May, the federal government has begun returning to the field to kick-start new projects.

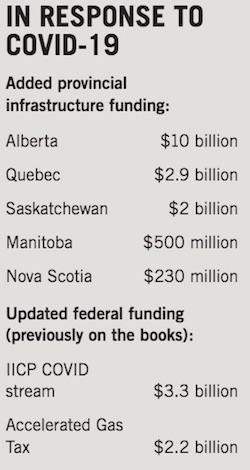

Ottawa has also created a separate COVID-19 stream under the IICP that focuses on getting pandemic-related infrastructure built more quickly. In May, Infrastructure Minister Catherine McKenna said the government is setting aside up to 10 per cent of the $33.5 billion provincial-linked IICP stream to address infrastructure challenges laid bare by COVID-19. Amending previous provincial agreements struck with Infrastructure Canada, the stream will see the feds pick up a larger share of project costs.

The federal government has remained non-committal on other added spending or changes to the IICP, so far, but Ferreira anticipates a stimulus plan will emerge this fall.

ADDITIONAL HELP

With little movement from Ottawa, half of Canada’s provinces have taken unilateral action.

Alberta, Manitoba, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan have already announced stimulus spending as a result of the virus. With the pandemic near its worst in mid-May, Quebec also added $2.9 billion to its 2020-2021 capital plan.

Other regions have been more reluctant to increase funding at a time government revenues are under considerable pressure. Ontario, for instance, has committed to sticking to its pre-pandemic pipeline for major P3 projects, but thrown cold water on the idea of adding to it.

“We can be assured with this big pipeline that we have announced and are reconfirming that we have a very big stimulus package happening right here in the province of Ontario that we are determined to continue with,” Laurie Scott, the province’s minister of Infrastructure, said during an online event hosted by the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships (CCPPP) this June.

While work on megaprojects in Ontario and elsewhere will continue, Webster anticipates much of the short-term stimulus funding will go toward repair and maintenance work.

“A lot of the investment is being targeted at the areas of state of good repair projects and those sorts of things, which are the right projects to get people working quickly,” he says, adding that the regulatory process makes it tough to get major new projects off the ground quickly.

The pandemic may also help boost the Canadian government’s long-term push to shift private capital into infrastructure work.

With some of the lustre off the real estate market, at least for the short-term, Gill sees infrastructure as an attractive, safe alternative for deep-pocketed investors.

State of good repair projects will likely see a major boost from the stimulus funding. PHOTO: Adobe Stock/Gajus

“There’s a lot of financial investors, like pension funds, sovereign wealth funds… insurance companies that are looking to park their money,” he says. “Historically, they’ve had to go international because there wasn’t really this appetite to build new infrastructure projects in Canada.”

But with Ottawa and individual provinces looking to finance new infrastructure to put people back to work, as well as address the country’s worsening infrastructure deficit, Gill says encouraging private capital into infrastructure would be a win for both parties.

The Infrastructure Bank was created partly for this very purpose. So far, the crown corporation has announced 10 projects it is working on in some capacity. About half of these projects have funding attached, but the bank remains well below its goal of deploying $35 billion into new infrastructure work.

A NEW REALITY

About six months after Canada reported its first COVID-19 case, provincial governments appear to have largely contained the virus, but the return to normal still looks distant.

Contractors have adapted, bolstering health and safety protocols to keep staff safe, as well as turned to technology to modernize long-established ways of working. The continued embrace of cloud technology to better connect job sites to head offices, improve documentation and eliminate contact points during material deliveries, are just a few examples.

Webster sees the pandemic as an opportunity for infrastructure planners to bring similar improvements into the procurement and project delivery process.

“Government could use this to help transform the industry,” he says, pointing specifically to the opportunity for better collaboration between owners and contractors and what is increasingly seen as a risk-sharing mismatch on P3 projects.

The uncertainty on what projects will be required in the future also extends beyond transit. Ontario recently cancelled a major courthouse project, for instance, saying it will instead look to “new and innovative ways of delivering justice remotely and online.” The same dilemma applies to areas such as virtual healthcare and education.

“A lot of the [infrastructure] was planned quite a few years ago, based on traditional ways of doing things,” Webster says. “I’m just not sure what the new economy’s going to dictate and drive as people realize that some of those plans are going to have to change,” he says. “I think government is going to have to be a little more flexible in some of those programs.”

This article first appeared in the August 2020 edition of On-Site. Read through the complete issue here.

It is also one component of On-Site’s 2020 Infrastructure Report. The complete report is available here.