Bridging Canada’s busiest road: Crews cap off distinctive pedestrian span over Ontario Hwy. 401

By David Kennedy

Bridges

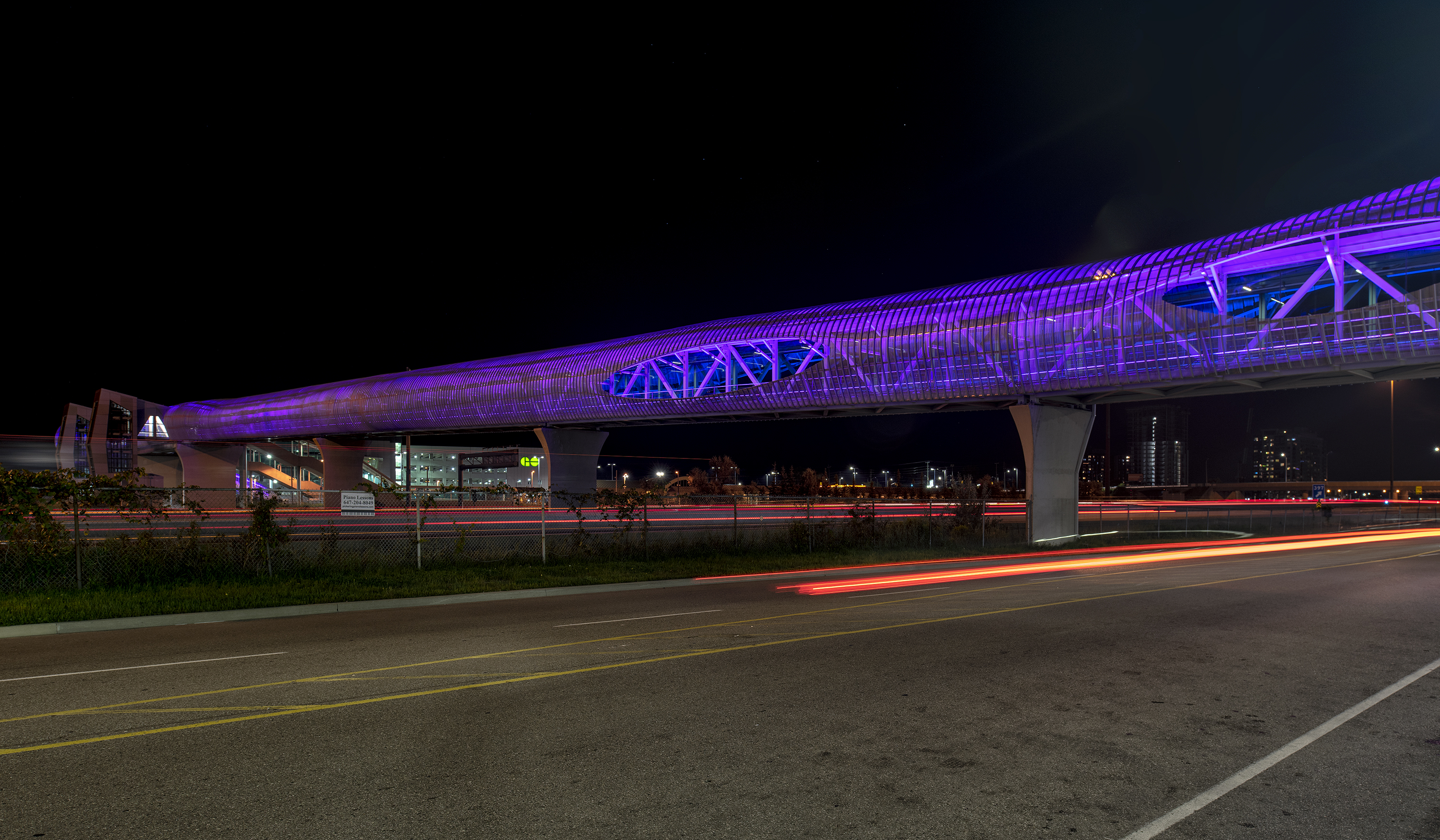

The bridge is encased in a mesh-like aluminum cladding known as Kalzip and is outfitted with an LED lighting system (PHOTO: Metrolinx)

Leapfrogging 14 of the busiest traffic lanes in the country, six railway tracks and a city street, the pedestrian bridge over Highway 401 in Pickering, Ont. is one of the longest enclosed footbridges in the world.

After nearly eight protracted years of construction, crews officially wrapped up work on the new span Sept. 21.

The distinctive bridge stretches 250-metres from end to end, connecting a bustling commuter parking lot with the Pickering GO Station south of the highway. It’s also frequented by students and shoppers bound for college classes or Pickering Town Centre.

While the bridge opened to foot traffic in 2012 – little more than a year after crews broke ground – a string of setbacks, including trouble with the original contractor, kept it under construction until this fall.

“This pedestrian bridge was a first for us, for the province, and even for Canada in regards to providing a significant connectivity solution over well-established and heavily-used infrastructure,” says Metrolinx spokesperson Scott Money.

Spearheaded by the provincial transit agency and its subsidiary GO Transit, early construction involved the installation of seven separate box trusses to span each segment of road and rail. Contractors built concrete piers between sections of the 401’s express and collector lanes to support the huge trusses before using a crane to lift the purpose-built metal sections across the highway.

The trusses provoked significant controversy when Ontario Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk released a scathing report in 2016 about oversight issues on the bridge project. Among other issues, the report stated one of the trusses had been installed upside down.

PHOTO: Metrolinx

Metrolinx admits to running into numerous problems during construction, but denies one of the trusses was inverted during installation. In a Q&A session put on by the transit agency, Roberto Sguassero, a project manager for the job, said it would have been “virtually impossible” to assemble the bridge with one truss flipped 180 degrees.

The report did lead to changes to Metrolinx’s procurement process, however. The agency vowed to put existing contractors under closer scrutiny, as well as factor past construction performance into bids for future work.

Despite the public spat over the flipped truss, it was the bridge’s more superficial features that have led to the lengthy delays. By the time the auditor general’s report was released nearly two years ago, the bridge was already well behind schedule and Metrolinx had terminated its contract with the initial contractor.

Among other issues, the contractor caused serious damage to the bridge’s glass panels when it failed to protect them prior to welding. Many of the sheets needed to be replaced.

The new glass was finally put in place last summer and crews worked to put the finishing touches on the bridge’s outer coverings over the past few months.

It was a long road for the relatively short bridge – and the significant delays took their toll on the project’s budget. Metrolinx says the final cost of the project reached $38 million, up from an expected cost of $22.5 million when construction began in 2011.

Still, the project was far more ambitious than most.

Unlike typical highway overpasses along the 401 corridor, which are strictly utilitarian, designers of the Pickering bridge made the appearance of the final structure a key factor in the plans. Along with serving some 9,000 commuters boarding trains at the Pickering GO each day, the bridge is designed as a showpiece for the growing city east of Toronto.

An LED lighting system, similar to the one that illuminates Toronto’s CN Tower and other landmarks around the world, lights up the exterior of the span. The bridge is also encased in a type of mesh-like aluminum cladding known as Kalzip. The material, more commonly used as roofing, coils around the outermost section of the bridge like a shell.

“The Kalzip cladding system gives the bridge its iconic form and controls the solar heat for customers,” Money says. “Kalzip is also energy-saving and weather-resistant and allows for visibility and light – the interior of the bridge structure is never dark, so people walking through it are always visible.”

Flipping the switch on the LED lighting system, top Metrolinx brass, as well as local and provincial politicians officially wrapped up the project Sept. 21.

This article first appeared in the October 2018 issue of On-Site. You can check out the full issue here.